After an excellent lunch in the staff canteen, we assembled in a conference room to hear about key dates and achievements since the Met Office was founded by Robert FitzRoy in 1854:

It was interesting to note the increase in the Met Office’s computing power over the years:

Today the Met Office is a globally relevant, world-leading organisation:

- 1909: Introduction of telegraphy meant forecasts could be sent wirelessly.

- Post World War I: Lewis Fry Richardson developed a gridded map system which brought mathematics into forecasting and formed the basis of the modern weather forecast.

- June 1944 (D-Day): British forecasters correctly predicted a very narrow window of fine weather in which the Normandy landings could take place.

- 1953: January storm surge led to greater efforts to forecast storms and ultimately the construction of the Thames Barrier.

- 1960s: Satellites began to provide “bird’s eye” views of cloud swirls; the European satellite was launched in 1977.

- 1987: The ‘great storm’ (NB not a hurricane) led to the development of national weather warnings aimed at the general public (rather than the Ministry of Defence or maritime services).

- 1990: Establishment of the Hadley Centre, which focuses on climate change research and works closely with the IPCC.

It was interesting to note the increase in the Met Office’s computing power over the years:

- 1959: Met Office’s first supercomputer, Ferranti Mercury, capable of 30,000 calculations per second.

- TODAY: Cray XC40, capable of 14 thousand trillion calculations per second.

- IN THE NEAR FUTURE: New supercomputing capability in partnership with Microsoft will be capable of 60 quadrillion calculations per second and will be carbon neutral.

Today the Met Office is a globally relevant, world-leading organisation:

- It serves weather information to many air traffic control providers.

- It forecasts severe weather such as hurricanes and cyclones to insurers.

- It works with aid agencies on crisis response and capacity development.

- Today’s four-day forecast is as accurate as the one-day forecast 30 years ago.

|

We then split into three groups for tours of the building and grounds.

We were led across the ground floor of the building, along an area called the Street. We could look all the way up through the atrium to meeting rooms and offices above. There was a stream running through the street, and positive posters all around, of different members of staff describing their jobs. It felt like an exciting and friendly place to work. |

|

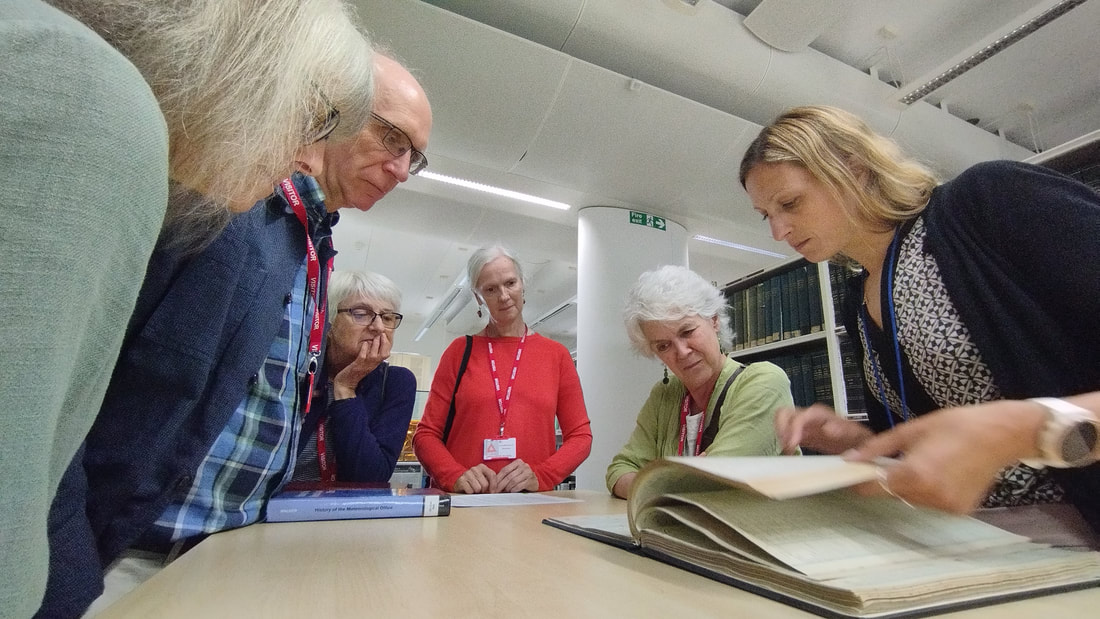

In the Library we looked at displays of elderly weather monitoring equipment and leafed through records and weather maps – some of us found out what the UK weather was doing on the day of our birth.

|

At the end of the Street we found the Studio, where a daily weather forecast had just been recorded for the Met Office app. A fun moment, where I got to stand in front of the green screen and pretend to present the weather.

|

Then into the bowels of the building for a quick peek at the Met Office’s supercomputer, behind firmly locked doors, doing anything up to 14 thousand trillion calculations per second without breaking a sweat, apparently.

Then to the Operations Room, which, even though many staff do work from home, really felt like the beating heart of the whole place. What a buzz! There were huge TV screens showing breaking global news and changing weather maps for those folk responsible for communicating crucial weather info worldwide.

We spoke to a member of the flood resilience team seconded from the Environment Agency. And then a chap whose screens showed real-time images of our star, the sun! We’d found a space weather-man. He told us that we are about two years away from a solar maximum. That’s a high point of solar activity over a cycle of on average 11 years. The Met Office monitors solar flares and coronal mass ejections, which can impact negatively on satellites and electrical equipment. We learned that the Carrington Event which occurred in 1859, was one of the largest geomagnetic storms ever recorded. It seriously disrupted telegraph communications, and if a similar event occurred today, it would be potentially very serious. So space weather watching is vital.

And finally, a wander outside, past a small collection of bee orchids, to check out a huge array of weather monitoring equipment. Yes, there are cameras on satellites pointing at the sun and sending images of its boiling surface back to the Ops Room. But the recording and collecting of actual analogue weather (rain, snow, dew, fog, wind, sunshine…) is also a key part of the Met Office’s job.

Then to the Operations Room, which, even though many staff do work from home, really felt like the beating heart of the whole place. What a buzz! There were huge TV screens showing breaking global news and changing weather maps for those folk responsible for communicating crucial weather info worldwide.

We spoke to a member of the flood resilience team seconded from the Environment Agency. And then a chap whose screens showed real-time images of our star, the sun! We’d found a space weather-man. He told us that we are about two years away from a solar maximum. That’s a high point of solar activity over a cycle of on average 11 years. The Met Office monitors solar flares and coronal mass ejections, which can impact negatively on satellites and electrical equipment. We learned that the Carrington Event which occurred in 1859, was one of the largest geomagnetic storms ever recorded. It seriously disrupted telegraph communications, and if a similar event occurred today, it would be potentially very serious. So space weather watching is vital.

And finally, a wander outside, past a small collection of bee orchids, to check out a huge array of weather monitoring equipment. Yes, there are cameras on satellites pointing at the sun and sending images of its boiling surface back to the Ops Room. But the recording and collecting of actual analogue weather (rain, snow, dew, fog, wind, sunshine…) is also a key part of the Met Office’s job.

All this data, collected by professionals and amateurs over the years, since the days of Luke Howard and beyond, and still being collected today, feeds into the Met Office’s mathematical model of the atmosphere that continuously informs and improves their forecasting.

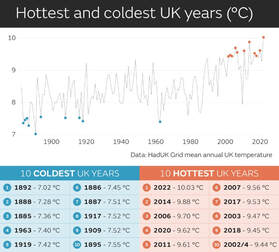

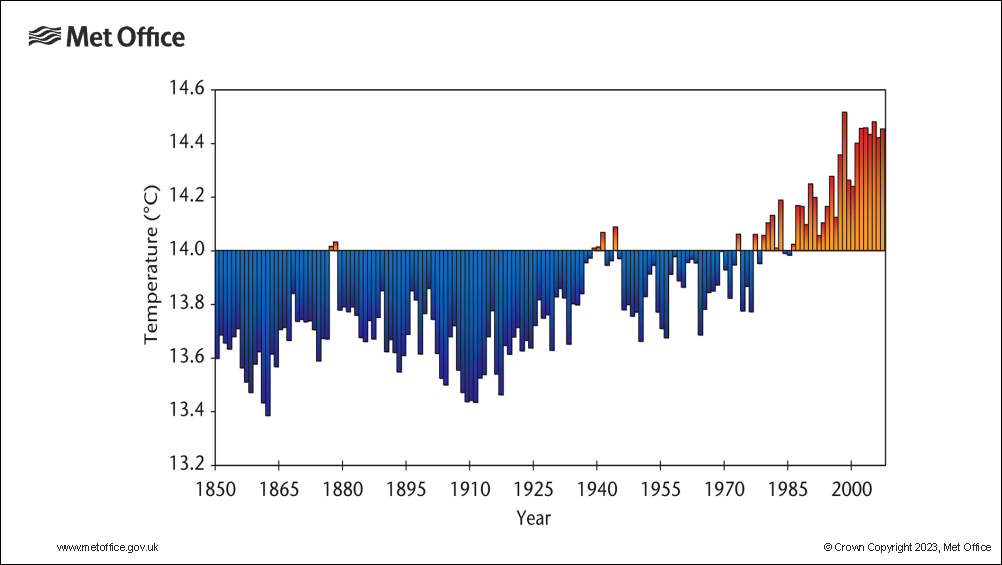

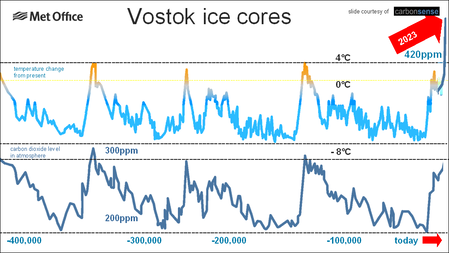

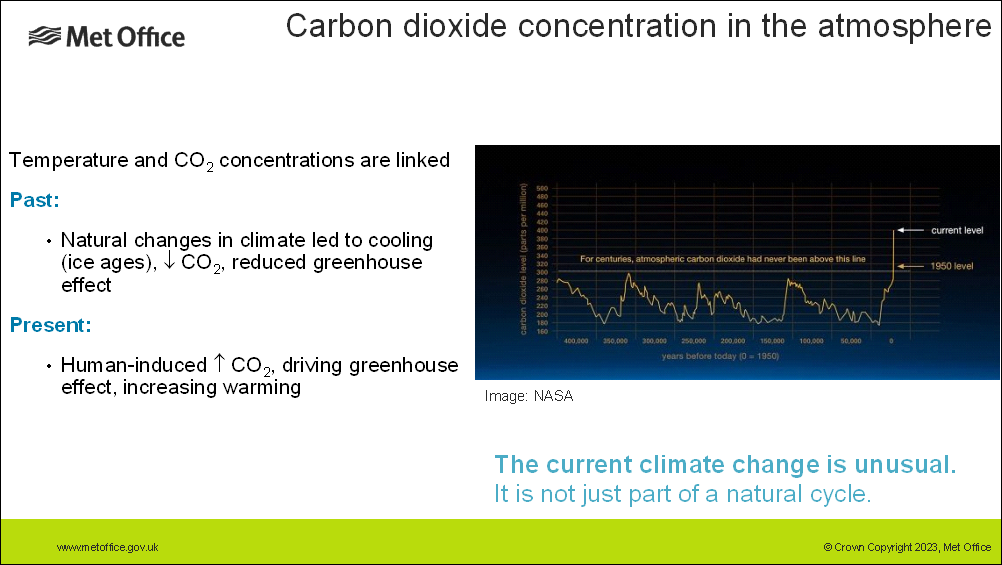

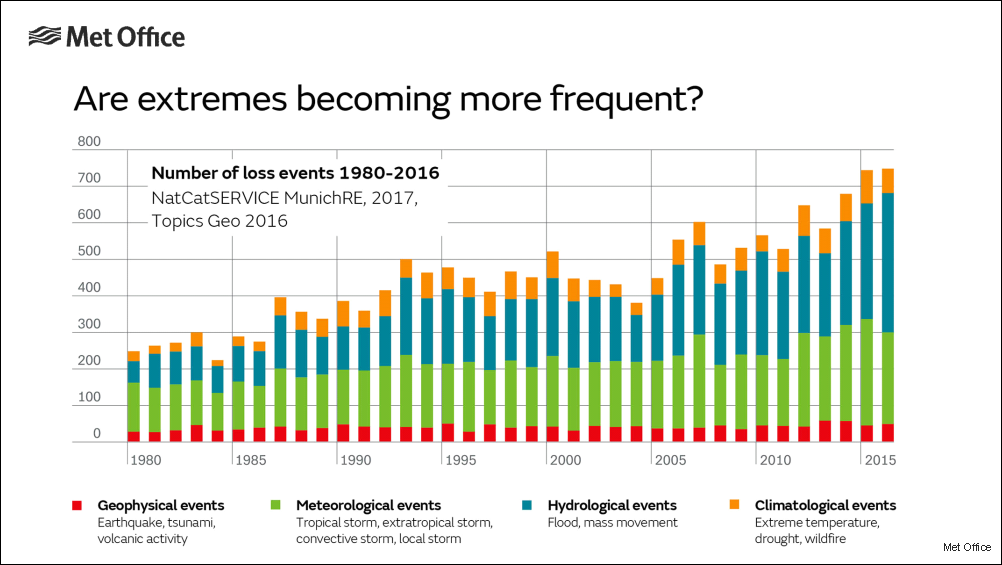

The data also tells us unequivocally how the global climate is warming. Analysis of the Vostok ice cores shows that atmospheric CO2 right now is at extremely high levels. The current changes to our climate are unusual and not part of any 'natural cycle'. 'Extreme loss' events such as extreme heat, severe flooding, drought and wildfires are becoming more frequent. As the meteorologists we spoke to at the Met Office told us, "the next decade is crucial for bringing down emissions".

The data also tells us unequivocally how the global climate is warming. Analysis of the Vostok ice cores shows that atmospheric CO2 right now is at extremely high levels. The current changes to our climate are unusual and not part of any 'natural cycle'. 'Extreme loss' events such as extreme heat, severe flooding, drought and wildfires are becoming more frequent. As the meteorologists we spoke to at the Met Office told us, "the next decade is crucial for bringing down emissions".

|

Many thanks to the Met Office for hosting us, and in particular to their staff members Helen Roberts for organising the visit and Amy Bokota and Jonathan Vautrey who joined Helen in looking after us all afternoon. Text: Moira Jenkins Photos: Bob Chase |

|

Public Open Days

The Tottenham Clouds tour of the Met Office was part of the Luke Howard 250 anniversary programme.

The Met Office currently have no further Open Days planned.

If you would like to receive further information when new dates become available,

please complete the Public Open Days form.

The Tottenham Clouds tour of the Met Office was part of the Luke Howard 250 anniversary programme.

The Met Office currently have no further Open Days planned.

If you would like to receive further information when new dates become available,

please complete the Public Open Days form.